“OVERHAULING THE AMERICAN PRISON INDUSTRY: A View From 20 Years of Incarceration” is the name of the seminar that my co-author Maurice Tyree and I appeared on this morning. Hosted by our publisher, Lived Places Publishing, it was an opportunity for people to learn about our book, hear Maurice’s thinking, and simply understand why we wrote the damn thing, The Darkest Parts of My Blackness: A Journey of Remorse, Reform, Reconciliation, and (R)evolution.

The why? Essentially, to effect change. To humanize the people held in cages in this country who are being sold a bill of goods that they are part of a rehabilitative system that is more often than not a site of cruelty and dehumanization.

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

– Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

This was how Maurice led off, answering as to why people should care about what happens inside American prisons, why folks should wonder how roughly 1.8 million of their fellow citizens might be doing in there. I have had people remind me that some folks don’t believe criminals deserve any kind of “special” treatment, that they are paying dues for their wrongdoing and thus deserve the punishment they get. Yes, we know this belief system exists. In fact, good old “liberal” Blue-state California just voted down Proposition 6, which would have banned involuntary servitude in prisons. The 13th amendment is alive and well:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime…

See, we never actually rid our country of slavery. It’s right there in the ironically entitled Bill of Rights. If you haven’t already, please watch Ava DuVernay’s film 13th. It explains a lot, in a most powerful and stunning fashion.

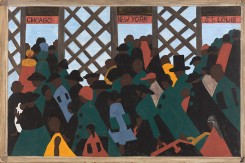

And guess what, you know who the majority of those involuntary servants are, Black people. You know why? It’s not because Black people are somehow more prone to crime, it’s simply that they are more prone to be exploited by the systems of racism in this country that place them in vulnerable positions which tend to be proximate to crime and criminal behavior. And of course, there is the fact that not everyone in prison is guilty. See the Innocence Project, as just one example of this fact. This is an injustice to so many. And, as Maurice points out, even if you don’t care what happens to them inside, they are eventually going to come out — and to a neighborhood near you. The previously incarcerated are present right now at the places you shop, work, and study. Wouldn’t you prefer to share those spaces with folks who have come out rehabilitated, instead of beaten down? Transformed, instead of hardened by anger? Hopeful instead of nihilistic?

Hope is something Maurice talks about a lot. Someone in the chat, during our seminar, asked how a prisoner could find hope in such a dark place. His answer: hope. Hope breeds hope. He calls it a revolution within that ultimately creates a revolutionary without. That is what he did with himself, but not everyone can. The point is that one should not have to be the smartest, most resilient human alive just to come out of prison with a chance at a redemptive life. Because most of us aren’t all that. That’s one reason he wanted this book to get published:

In the January 2012 letter to [my sister] Marquetta, I mentioned a “book writing idea.” What you are reading is basically the result of that idea. I wanted to “seek some form of liberation within the reader’s mentality” [as written in the letter] because I knew that people’s minds would need to be freed from a lot of preconceived notions. I wanted to encourage people to work hard to understand other people, people they didn’t know but maybe still had opinions about (59).

Education is a large theme in the book. How it’s denied, how it’s defined, how one snatches it up where one can. In our book, there are essentially three voices: one comes in Maurice’s letters that he wrote to family, friends, and associates while incarcerated; the second voice appears in his reflections on these letters as he re-reads and reconsiders them at the present; and the third voice is mine, providing historical and social context – and commentary – to all of the above. The Introduction begins with Maurice’s Compassionate Release Letter. It was submitted at the height of the COVID pandemic, when the prisons were veritable breeding grounds for infection. Over 6,000 incarcerated people died in the first year of the pandemic alone. Maurice had major health issues, already undergoing heart bypass surgery in prison.

In his letter to the presiding judge, Maurice addresses concerns expressed previously by that judge about his educational accomplishments (or lack thereof) while incarcerated. I provide this context:

Education is a complicated term, one that carries a very singular meaning for many people. Mr. Tyree, referencing Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book, Between the World and Me, explains that, like Coates, he was never much of a classroom person, even as he had definitely become a book person. Coates writes, “The pursuit of knowing was freedom to me, the right to declare your own curiosities and follow them through all manner of books. I was made for the library, not the classroom. The classroom was a jail of other people’s interests(17).

Later he writes about how he sought out his own education:

I grew so much once I started reading about the ideas and lives of different people, especially the writing of Black thinkers and activists that I never heard of in school. They were the door to my mental liberation and I wanted others to take that journey, too (60).

And finally, he sums up education like this:

Everything we do in life can be considered school. School is school, but so is growing up in a rough neighborhood, selling drugs, and going to prison. I have chosen to learn from all my schooling, and I keep on learning now that I’m out. What I learn I like to pass on to others, maybe save them a couple years or so. And my brothers do the same for me. I have learned all manner of things in these life classrooms. It’s all about exchanging information and ideas, that’s how we grow and learn. That’s how we create community. That’s human connection (212).

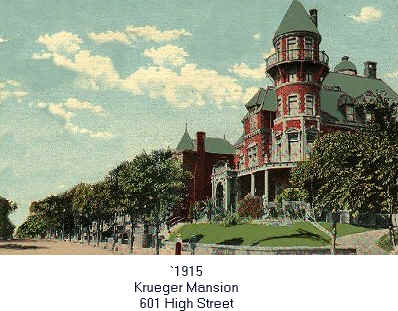

I had two books come out this summer. And as distinct as they might seem at first glance, they are really quite the same. Alien Soil: Oral Histories of Great Migration Newark foregrounds stories of African Americans who came to Newark during the Great Migration. In their words, through oral history interviews, they describe an event, place, and time that is often left to outsiders to explain. Same goes with this book with Maurice. There is much scholarship, journalism, and political punditry surrounding America’s prison industrial complex. But this book provides explanation from one with lived experience. Fortunately, this practice is becoming a bit more common regarding the prison system, as newsletters, podcasts and journals surface, ringing with the voices of the incarcerated, as well as of those who have found their freedom — in one way or another.

I understand my assignment, as they say. It is to provide historical framework and social context for the narratives of Black Americans whose stories continue to be buried and just plain erased. Perhaps the reader will take on the assignment of listening to some of those voices. This seems all the more urgent in light of the recent changing of the guard in our American political system.