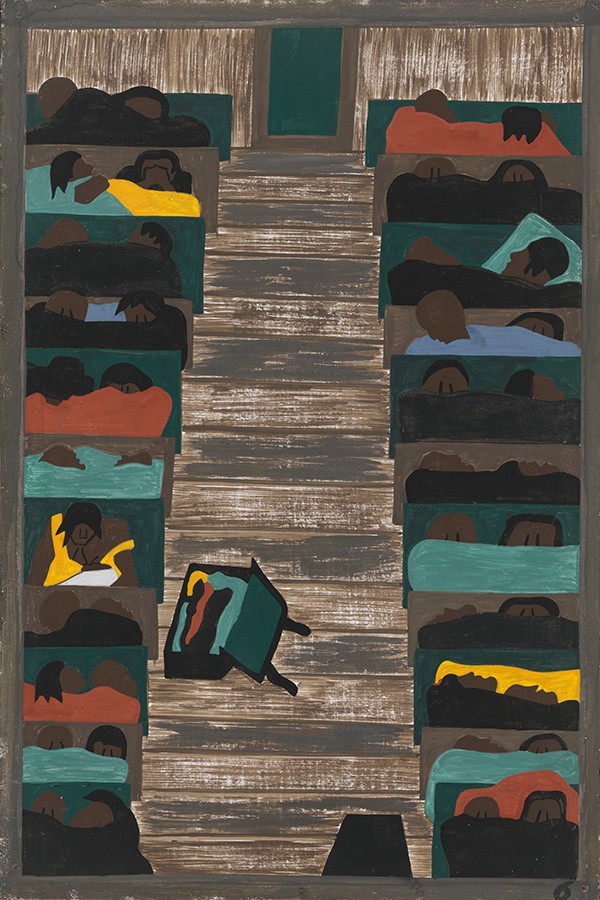

RACIST TRANSPORTATION REGULATIONS of the early/mid-20th century South resulted in African-American travelers often being herded into cramped Jim Crow cars, mostly banned from moving about the train for the next few days. Standing-room-only was often the case, at least until the trains crossed into the North, where segregation was less prevalent, and some freedom of movement became available. Stories from my book, Alien Soil: Oral Histories of Great Migration Newark explains some of these geographical demarcations, wherein Black passengers were finally allowed to relocate into other more roomy train cars. During travel from the South to the East, that usually came somewhere around Washington, DC.

George Branch, longtime Newark city council member – born in 1928– recalled his family’s train trip from North Carolina to Newark when he was a child:

…My mother was able to save up the little money that we made, you know, on the farm. And my aunt, I think she contributed to it…The train was clean. The porters was very nice and courteous …Most all of them Black in those days… They help you with your luggage and your bag and getting on the train, you know…They had food available, but we packed our little food from down home. We packed it in a shoe box. We ate chicken, ham, biscuits, you know. And all that wrapped up in a shoe box…So, you know, you ate when you got ready. So you didn’t have to go order anything and pay for it…The trains was segregated in those days and times…The whites and the Blacks are not sitting together on the train at all. Called a Black section, you know. All Black folks. You know, we had all our boxes and bags piled up, you know, all over the place…

While Branch believed they had carried their food from home simply for convenience, there is a good chance that at the time of his trip there would have been little to no access to food on the train for the “colored” passengers. Many stories in my book speak of those shoebox meals, carried on trains, and transported by car along the journey. This practice was so engrained that for many even decades later, they still made sure to have something to eat with them, “just in case.”

Many of these segregation rules were fairly new, implemented by Southerners in order to staunch the exodus of African Americans and their cheap labor. All sorts of ordinances were enacted — against purchasing more than one ticket at a time, for example, stopping families from leaving all together. Or passengers would simply be turned away at the station, and pre-paid tickets refused. Sometimes the ticket agent just would not get to them in time to make their train, having served the white passengers first. Some Black travelers would then be provided the “opportunity” to pay extra for purchasing a ticket on the train. Yet other times migrants might even get “ratted out” by friends and family, hoping for some sort of leg up with the white people in power. Not to be discouraged, some African Americans would travel to a more distant train station, in the hopes of not being recognized or meeting up with law enforcement. All of this effort was made simply to gain access to an often difficult and sometimes dangerous trip.

Notably, even if the travelers did make it through this gauntlet to the station such that they were actually able to wait for their train, the segregated waiting rooms provided a preview of the accommodations to come. Often there would be waiting rooms for men, waiting rooms for women – and then waiting rooms for “Negroes.” This was typically the case on the trains, too. (See the story of Ida B. Wells being thrown out what some sources say was the “Ladies’ Car”). The station restrooms had the same delineations, such that when Black women wanted to use the facilities they would need to bring another woman with them, for privacy and even safety. This treatment could continue right on through to the physical boarding of the train as Black passengers were forced to hoist themselves and their luggage up onto the train without benefit of the same equipment offered the white passengers:

And as the Jim Crow car became entrenched, Black passengers lost access to the step. At small stations, according to W. E. B. Du Bois, southern railroads began to stop the Jim Crow car, which was invariably the first passenger car, “out beyond the covering in the rain or sun or dust,” and require Black passengers to climb on and off without even providing a step.

-W. E. B. Du Bois, “On Being Black,” New Republic, 21, no. 272, February 18, 1920

While we think of the back-of-the-bus rule applying to most segregated transportation, the front car on the train was often the one where Black migrants were relegated to. As DuBois notes, it was typically less shielded from the elements – including the soot and smoke emanating from the engine. Often wearing their best clothes, many migrants would finally arrive at their destination in a state of dishevelment. And so the vicious cycle continued, as established citizens looked upon these new migrants with disgust or trepidation.

So was the journey for many – and yet not all – African Americans leaving the South for better jobs and physical safety, among other things. Recall that not every migrant was the same; from economic class to geographical location, these journeys depended upon many factors. But the story told here, and those in my book, reflect a large part of the migration experience.

If these stories pique your interest, I highly recommend the book Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance byMia Bay. And to learn more about the Great Migration from those with the lived experience, pick up my book full of oral histories. There are, of course, other sources as well, including PBS’ recent Great Migrations: Great Migrations on the Move. It includes the contributions of a number of historians, including two of my favorites, Davarian Baldwin and Brittney Cooper. And yet, as so many urban centers across the North and East, and even west, are referenced in this fine program, Newark is only spoken of twice (of course I counted): as a “hell,” and then with regard to the 1967 uprising. This, of course, supports my thesis that these stories need to be told, to be passed on, and to be integrated into the greater Great Migration historiography. Let it be so.