CHRISTMAS IN NEWARK’S GREAT MIGRATION ERA could, of course, be merry and bright just like anywhere else. Military Park, downtown, for years had a huge, decorated tree, replete with a life-size nativity scene. And the famous Public Service building was lit up dramatically each year.

But Christmas also could have a more somber side. For example, not everyone had access to jobs that paid well enough to buy those presents and prepare those meals that are seen by many as requisite to the holiday’s celebrations. In fact, when one views the photographs that show up when searching Newark at Christmastime early-to-mid-20th century, not many African-Americans appear at all. It was really not until the 1960s that they are seen regularly included in seasonal newspaper images and promotional materials. Segregation and discrimination was not taking a holiday break.

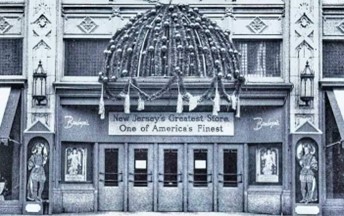

Katheryn Bethea, who at sixty-years-old finally completed the college degree she had started back in the 1950s, ultimately retired as a professor of English literature. Like so many of the Krueger-Scott narrators, she often had a rough hill to climb just to get some work to pay the bills. Mrs. Bethea recalls in her interview one Christmas season, in 1942, when she sought to supplement her income by working at the famous Bamberger’s department store. She did get work, but was hired as a “floor girl,” carrying up clothing from the basement to the various departments. This was one of the more low-paying jobs at the store. Now, because of her diligence as an employee, Bethea was actually asked to stay on after the holiday season. She agreed to do so, but only if she could work as a salesclerk instead of carting around stock all day. She said:

They weren’t hiring any Black women – girls…to be clerks. We could go down there and lug all that stuff…

The position of salesperson was not available to women who looked like Bethea. Her manager told her that while she was personally ready for an African American “on the floor” that Bamberger’s was not quite there yet. Bethea declined the store’s offer of continued employment.

Another issue that might put a damper on Christmas came from living in poor housing conditions. For many Black Newarkers some traditional rites of the holiday turned out to be dangerous pursuits. Retired musician James “Chops” Jones remembered:

Oh Christmas. Oh, let me tell you about Christmas. Christmas we used to have real Christmas trees. It used to have candles on them. And we used to light the candles on the tree… But on the branches we had little dishes, you’d put the candle in like the birthday candle, you put the candles in and you light ‘em.

Owen Wilkerson, one-time city clerk, remembered this tradition as well – and how, when he was growing up, fires were commonplace because of it.

And, you know, for some strange reason, and I guess it was attributed to the Christmas decorations and the trees. I mean, everybody had a tree at Christmas. But fires would always- You would always have an excess amount of fires around the Christmas holidays.

In my book, Alien Soil: Oral Histories of Great Migration Newark, there is a whole chapter dealing with fires and the precarity of living in subpar housing. Disasters due to poor infrastructure took no holidays either.

For the majority of people interviewed for this oral history collection, the Christmas holidays were a time to do what you could with what you had; a time to be with family, share food, and exchange gifts if one could afford to do so. For a long while Black Newarkers were not celebrating the winter holidays in the same ways—or in the same spaces — as white Newarkers. There were, however, always exceptions; that’s what oral histories are so good at reminding us of.

Madam Louise Scott, philanthropist and beauty culture millionaire, would throw lavish parties in Newark every year at Christmas. She took this time to provide fun — and gifts — to so many African-American children who otherwise might not have received a whole lot of either. Below is a promotional postcard made by some of the people trying to have her mansion turned into a Black Cultural Center after her passing in the 1990s. As you can read in chapter one of my book, that project’s story in and of itself is quite a dramatic one.

Today, many of us are attuned to the fact that our Christmas season may not look like others’. It’s often a time when those with excess resources give of their time or money to good causes for others less fortunate. And yet, perhaps in part due to a lack of exposure to history, there are those who cannot comprehend the trials of trying to keep up with the consumerism and lavish events surrounding this holiday season. For them, I present this little slice of life, an opportunity to keep learning our history.

And for all of us, let us never forget that some have much less than others. And if we are the ones with the least, let us remember that we are not alone.

Happier New Year to all.