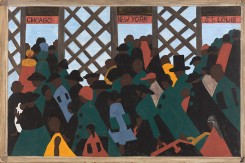

Panel 3: The Migration Series, Jacob Lawrence.

“SOUTHERN TOWN.” The term can evoke images of racism and violence. And this was the case quite often, through the 20th century – and of course still occurring even today. But, as oral histories are so wonderful in reminding us, nothing and no one is all one thing. And the interviews from the Krueger-Scott African-American Oral History Project that appear in my book also remind us that not every Black migrant left an agricultural life – another image we often see through depictions of this historical event. After all, some folks came from the cities; they abandoned spaces both rural and urban, as they headed north, east, and west. And while this Migration may have started out “by the hundreds,” in the end approximately six million humans uprooted themselves, and their loved ones, from their homes to escape whatever it was they no longer could abide by. Hence a Great Migration. Below I am going to share some bits of discussion around this leaving. And, as you know by now, you can always order my book to read so very many more of these kinds of stories.

Louise Scott, who left Florence (probably), South Carolina in 1936, became a millionaire beauty culturist in Newark, NJ. She built an empire, running many businesses out of the Krueger-Scott Mansion on High Street (now MLK Blvd.). A foundation has been created to honor and continue her legacy, the Newark Scott Civic and Cultural Foundation. And many of the narrators in my book speak of Madam Scott and the Mansion; she was an integral part of the Black Newark community for decades.

Now, the City of Florence was chartered in 1871 by the Reconstruction government and ultimately named after a railroad magnate’s daughter. Florence was what many might imagine as a place African Americans would leave, if they could, for “a better life.” Sharecropping, for example, was a major occupation for many Black citizens, growing mostly rice and tobacco. And if you know anything about the system of sharecropping, then you know it was not really set up to benefit those who worked within it.

Attorney Eugene Thompson spoke about his mother working as a domestic while living in Norfolk, Virginia. But she moved to Newark, met her husband, and gave birth to her son. Eugene. Mr. Thompson’s father, a journalist, was born in Memphis, Tennessee, and just “followed the Mississippi River,” finally ending up in Newark, according to Thompson.

In 1923, Norfolk’s city limits were expanded as it annexed several cities, while also adding a naval base and miles of beach property. The Norfolk Naval Base grew rapidly because of World War I, and this created a housing shortage in the area. I would imagine that then, like now, those most affected by the housing shortage were the poor and working class. And at that time, that would mean a preponderance of African Americans.

Memphis, Tennessee is well known today for many things, including its music scene. I visited the city last summer on a civil rights tour. It was a hard place to be Black person for a very long time, even though many famous African Americans lived their lives in Memphis — including W.C. Handy and Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Cotton was still “king” there, even in the early 20th century – and racist violence was rampant, including lynchings.

Matthew Little, retired factory worker for General Motors, was born in Starr, South Carolina. In his interview, he was explaining differences between northerners and southerners in terms of attire:

“Oh, in the South you wore what they call overalls, with suspenders, and here they even wore coveralls, which covered the whole body, you know. And in the South, especially in the country, they wash their shirts and overalls and starch ‘em and wear ‘em on Sunday. Instead of dressing in suits and ties.”

Starr, South Carolina was founded in the late 1830s under the name Twiggs. It was renamed Starr in honor of Captain W.W. Starr, another railroad official. Like many southern cities it was an agricultural hub, with early 20th-century “stately” homes — as the publicity material called them — including the Evergreen Plantation. (You can have your wedding there, if you’d like). More than 400 individuals were enslaved at Evergreen Plantation over the course of 150 years. That’s a tough culture to break, and probably a tough place to be an African American, even decades later.

Mary Roberts, a retired Newark Public Schools teacher and one-time district leader of the South Ward, was also thinking of fashion in her interview. Her memories took her back to her childhood in Greensboro, North Carolina.

“My mother washed the little white girls’ dresses, and I would just admire them, they were so pretty. I think that’s why I have a lot of clothes now. Because I always said ‘One day I’m going to have those pretty dresses.’”

Sometimes it’s necessary to read between the lines when researching the history of American cities. For example, one piece of material states that between, “1902 and 1905, [Greensboro] was the largest cotton mill in the south and produced more denim than any other mill in the world. In the northeast part of the city, the Cones built hundreds of homes for their workers in villages surrounding their mills.” Consider who worked in these “mills” and what the housing was like. In my own book, a terrifying memory of cotton mill housing is recounted by one of the interviewees. And well, fast forward some decades to Greensboro’s famous “sit-ins” of the civil rights movement. Clearly, things had yet to improve there, as far as many African Americans were concerned.

Pauline Faison Mathis was born in 1932 in Clinton, North Carolina. Speaking of fashion, Mathis tried to get a job at the famous Bamberger’s department store in Newark, sometime around the early 1950s. But she was told that she “wouldn’t like it” because she was so educated. “That was the word going then, ‘You have too much education, you wouldn’t be too happy here,’” explained Mathis.

I came upon several history publications about Clinton that literally didn’t mention African Americans or Black people. This is how our history still gets told, as if they were never there. As if Pauline Faison Mathis’ family didn’t have a life in Clinton at one time. A particular name comes up regularly in searching the African-American history search of the city: Charles Clinton Spaulding. He was apparently known as “Mr. Negro Business” and established the famous Black insurance company, North Carolina Mutual. Oh, and in 2018 numerous unmarked graves of enslaved people were discovered in the town. So there’s that.

As Jacob Lawrence tells us, African-American migrants were leaving southern towns. Florence, Norfolk, Memphis… Starr, Greensboro, Clinton… This departure was done in such a manner that a name had to ultimately be provided for the situation: the Great Migration. It changed our country; African Americans transformed the United States. We need to understand how – and why. And so, until next time, let’s keep learning our history!