“The war had caused a labor shortage in northern industry. Citizens of foreign countries were returning to their native lands.”

Panel 2: The Migration Series, Jacob Lawrence.

WAR HAS ALWAYS BEEN GOOD FOR OUR ECONOMY. (And politicians know it, by the way). When WWI began — and again in WWII — some immigrants went back to their countries of origin to fight in those armies. This departure greatly affected urban centers like Newark, as they had been the sites of so much early European migration. The industrial revolution that this country was undergoing at the time is an era of major transformation, especially in the cities.

Newark, New Jersey was a major hub of military supply manufacturing and shipping during both wars. In fact Newark was held up as an early example of modern industry such that an exposition was held in the city in 1872, with President Ulysses S. Grant in attendance.

Urban America looks like it does now, for better and worse, in large part due to this revolution and its aftermath. And if cities are something you want to know more about, then you can always order my book and read about Newark as a microcosm of urban America!

So, at the same time that some immigrants are reverse-migrating, scores of American men are also going off to war. Most of these enlistees are white men who had been working decent jobs for a decent paycheck, in factories and other industrial locations. While Black men also enlisted, there were fewer opportunities for them as soldiers; most branches of the military were still segregated by race – or they simply barred Black men altogether. In addition, the assignments that Black soldiers did receive were most often at the bottom of the hierarchical ladder: kitchen work, menial tasks around dangerous weapons, etc. These, therefore, paid far less than other assignments.

Circumstances did not change all that much, even as WWII was declared. In fact, just one story illustrates the ways in which Black soldiers were treated during the second World War. It happened at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine, here in California. Basically, a large group of Black soldiers were forced to handle munitions they had no training for. Pushed by their superiors to expedite their work, a terrible explosion occurred, killing hundreds of people. 256 of those Black soldiers were court marshaled while most of the white men involved were simply given leave. However, just this year, these men were exonerated – of course posthumously, as is often the case with reparations for African Americans.

Naturally, there are always exceptions to these tales of subservience and exploitation, including the famous WWI “Harlem Hellfighters.” But we must understand that even they did not achieve their status without conquering a myriad of obstacles along their way.

So it is wartime in America and the country is full of factories and other industries in need of laborers. At the same time, African Americans are continuing that Great Migration towards exactly these urban centers where the work exists. The labor shortage benefited African Americans, as well as women, for a time being anyway. They finally were able to enjoy some access to the kinds of well-paying jobs they probably never would have otherwise due to discrimination.

While Jacob Lawrence notes in his caption that there was most certainly a labor shortage, the Krueger-Scott oral histories tell us that not everyone could just suddenly waltz into one of these high-paying jobs now:

Willie Bradwell started working as a domestic when she first came to Newark in 1939, at the age of eighteen. She did not like domestic work, neither the tasks nor some of the people for whom she worked. “I hated it. I don’t like housework, not even my own,” she told her interviewer. One day her employer insisted that Bradwell get all her work finished before eating lunch. “So when I had my lunch it was time to come home…” said Bradwell. “I didn’t go back.”

Bradwell next found some factory work, which she liked much better. She started out at a paper-cup factory in North Newark at 55 cents an hour, minimum wage at the time. After a few months she secured a better factory job, with H.A. Wilson at 97 Chestnut Street, sometime around 1946.

“…they didn’t even hire Black people ‘til after the War. So when we went in there after the War, it wasn’t too much of a problem.”

The racial make-up at H.A. Wilson was about 25% Black and 75% white, Bradwell reported.

Notably, according to Bradwell the factory was not hiring African Americans during WWII. This therefore implies that other businesses may also have been willing to suffer through ongoing wartime labor shortages, simply in order to keep the racial status quo.

For many of the narrators in my book, factories were the promised land of better pay and working conditions, a big reason for leaving the South for the industrial North, East and West. Matthew Little was born in South Carolina and came to Newark in 1947, after finishing his tour in the Navy. (In 1944 the Navy commissioned its first-ever African-American officers. Things were changing, however slowly). Little worked on the factory floor at General Motors in Newark for thirty-two years.

Louise Epperson, after working yet another domestic job in nearby Montclair (the town I myself lived in for 20 years), landed a job at the Western Electric factory in Keraney, next door to Newark. Because of this relatively lucrative position, Mrs. Epperson was able to purchase her own home a few years later, a fact of which she was very proud.

Katheryn Bethea, who ultimately retired as an assistant professor of English literature at Rutgers University-Newark, worked multiple jobs in her lifetime – including at a dress factory when she was in need of extra money.

And Hortense Williams Powell told her interviewer that her family first received welfare, because Powell’s father had died in 1938, but later…

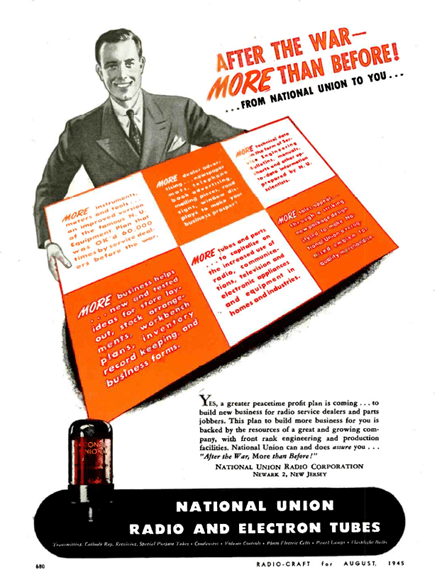

“…my youngest brother was old enough that my mother could go out and work, and she got a job at National Union Radio Tube Corporation. That was in Newark. And she worked there for ten years…They had labor problems, and the union walk-out, and all of that type of thing. It was after the War, the second World War… The factory closed down and it never reopened, and my mother stopped working. But by this time, this was about 1955, all of us were grown up then.”

Indeed, the 1950s saw the beginning of the end of the industrial revolution. A revolution that included many more human stories than most of us ever learned about in school.

Next week I’ll be highlighting some more of these interesting people and what they did with their lives once arriving from the south. Until then, let’s keep learning our history!