I HAVE A NEW BOOK as some of you know, out from Rutgers University Press: Alien Soil: Oral Histories of Great Migration Newark. Last year I spent some time writing about the subject matter of my book through the images of the painter. Jacob Lawrence’s, Great Migration series. So many readers enjoyed the art — whether as a reminder of how much they loved his work, or as introduction to a brand new artist. And I learned, through discussion around my book, that many people are just plain unfamiliar with the historical era and/or term, Great Migration. So, through images and words, I’d like to share stories of this pivotal time in American history. The dialogue included here comes from the oral histories contained within Alien Soil. And if you want to read more, well, then you can always order my book!

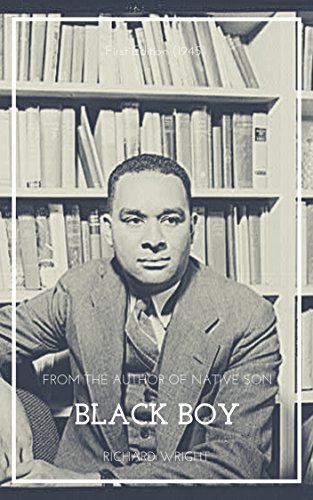

Today I want to start with some prose you might be familiar with; it is the inspiration for my book title. Have you read Black Boy yet?

Yet, deep down, I knew that I could never really leave the South, for my feelings had already been formed by the South, for there had been slowly instilled into my personality and consciousness, black though I was, the culture of the South. So, in leaving, I was taking a part of the South to transplant in alien soil, to see if it could grow differently, if it could drink of new and cool rains, bend in strange winds, respond to the warmth of other suns, and, perhaps, to bloom . . .

Richard Wright. Black Boy [1945 edition]

You might recognize the tail end of this quote, “…the warmth of other suns…” as the title of Isabel Wilkerson’s wonderful book on the Great Migration. And while the narrators of the Krueger-Scott African-American Oral History Project — the stars of my book — found warmth at times under the Newark, New Jersey sun, they also experienced quite often that they were living on alien soil. It didn’t look the same, feel the same, or even smell the same. And sometimes that was a good thing, but even good things can feel strange at first.

“The culture of the South,” as Wright puts it, takes shape in numerous ways for the participants of the Great Migration. In the discussions between narrator and interviewer in the oral history collection (who were always familiar with each other, which is unusual for an oral history project) we hear about the foods of childhood, chores performed that had no place in the concrete neighborhoods of Newark, and traditions clung to even while assimilating to Northern ways.

I always remember how you stop trains in the South at the location, build a fire by the railroad. The train stopped. We got on it…”

– Sharpe James, former Newark mayor

Folks sure didn’t have to do that in Newark — or in other major cities that so many Southern Blacks migrated to. After all, Newark’s Penn Station provided an organized system of trains, schedules, and ticket booths instead. Now, there are stories that some migrants, intending on living in New York City, errantly disembarked in Newark. Why? Because when the conductor, with his East Coast accent announced, “Newark, Penn Station,” it sounded very much like, “New York, Penn Station” to some. I have yet to find a person to attest to this through personal experience, but it makes for a good story, anyway. And isn’t that what history is, a chain of human stories fit together like puzzle pieces in order to create a bigger picture.

In her oral history interview, Senator Wynona Lipman, the first African-American woman elected to the New Jersey Senate, and the longest-serving member of the State Senate, was asked by Mrs. Glen Marie Brickus if she knew anybody who used snuff or chewing tobacco. Oral histories are so wonderful in the way that one question can often lead to an unlikely response. The great minds of the late historians Giles Wright and Dr. Clem Price created a questionnaire based on this understanding.

Lipman: Oh, the snuff, yes. Snuff, the lady who helped us do the washing, at the wash pot outside, you know, where you boiled your clothes for washing over a fire. Oh, she was a snuff dipper I tell you. And my father chewed tobacco. Yes.

Brickus: Oh yeah. Yeah, we had one of those wash pots in the backyard. And somebody had to go and build a fire on the wash day.

Lipman: I remember killing pigs, too. And making crackling.

Brickus: Oh really? Yeah, we did too, we did too.

Lipman: We had chickens, and all of that.

Brickus: We did too. We raised chickens and guineas and there was, you know, you’d wait for special kinds of days as far as the weather to kill hogs. And then you may kill three or four or more at a time. And I can remember seeing them strung up. You know, they’d put up these special poles, with the poles across the top and hang them up there.

Lipman: We had a smoke house.

Brickus: We did too. They would first salt the meat down for so long, and then take it out and hang it up and smoke it. Keep the fire going day and night to smoke the meat. And it would never spoil.

Lipman. No.

Brickus: You could keep it indefinitely and it would never spoil.

Lipman: It was wonderful. We had a cow until the town made us get rid of it. Senator Lipman concluded this conversation with an assertion that farming was a hard life, and Brickus ended this section of the interview saying, “Oh, we have more in common than we knew about.”

Talk about an opportunity to “see” the South in a way so many of us non-Southerners will ever get to. Now, granted this is the rural South, which is not what all of the land below the Mason-Dixon line looks like now – nor did then. Certainly, African Americans from the southern cities also left their homes for better jobs and somewhat less racism (although it often tended just to be more different than less). But because of a confluence of agricultural issues, especially around the early 1900s, those living off the land often had to leave that land behind. There will be more on this later.

Alright, thanks for reading the first installment of my own Great Migration series. Not as artfully done as Jacob Lawrence, but perhaps with the same intention: to ensure that the story of the people who left their homes for “a better life,” and in turn transformed our country for the better, get told. Tune in next time for a look at WWI and the Great Migration. Until then, keep learning our history!

Enjoyed reading this so much! Thanks for sharing and I can’t wait to read the book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re my first reader, thank you!!!

LikeLike